The Challenge

Global changes to insect populations are a reflection of mankind’s impact on the environment. Climate change, intensive agriculture and global trade have seen the demise of many beneficial insect species and the spread of insect pests. Some pest species can have huge impacts on crop production, while others vector human diseases.

One particular issue is the use of chemical insecticides which don’t discriminate between beneficial insects such pollinators and the pest species they are directed at. A smarter approach would be to devise a control strategy that only affects the target pest species, and leaves good insects like bees untouched.

The method

Each species of insect has its own gut microbiome. Certain bacteria have co-evolved with their insect hosts for thousands of years to form symbiotic relationships. For example, blood-feeding or sap-feeding insects each need their own specific symbiotic bacteria to provide them nutrients that are absent in their specialist diets. In turn, the bacteria can flourish by using nutrients ‘gifted’ by their host.

The impact

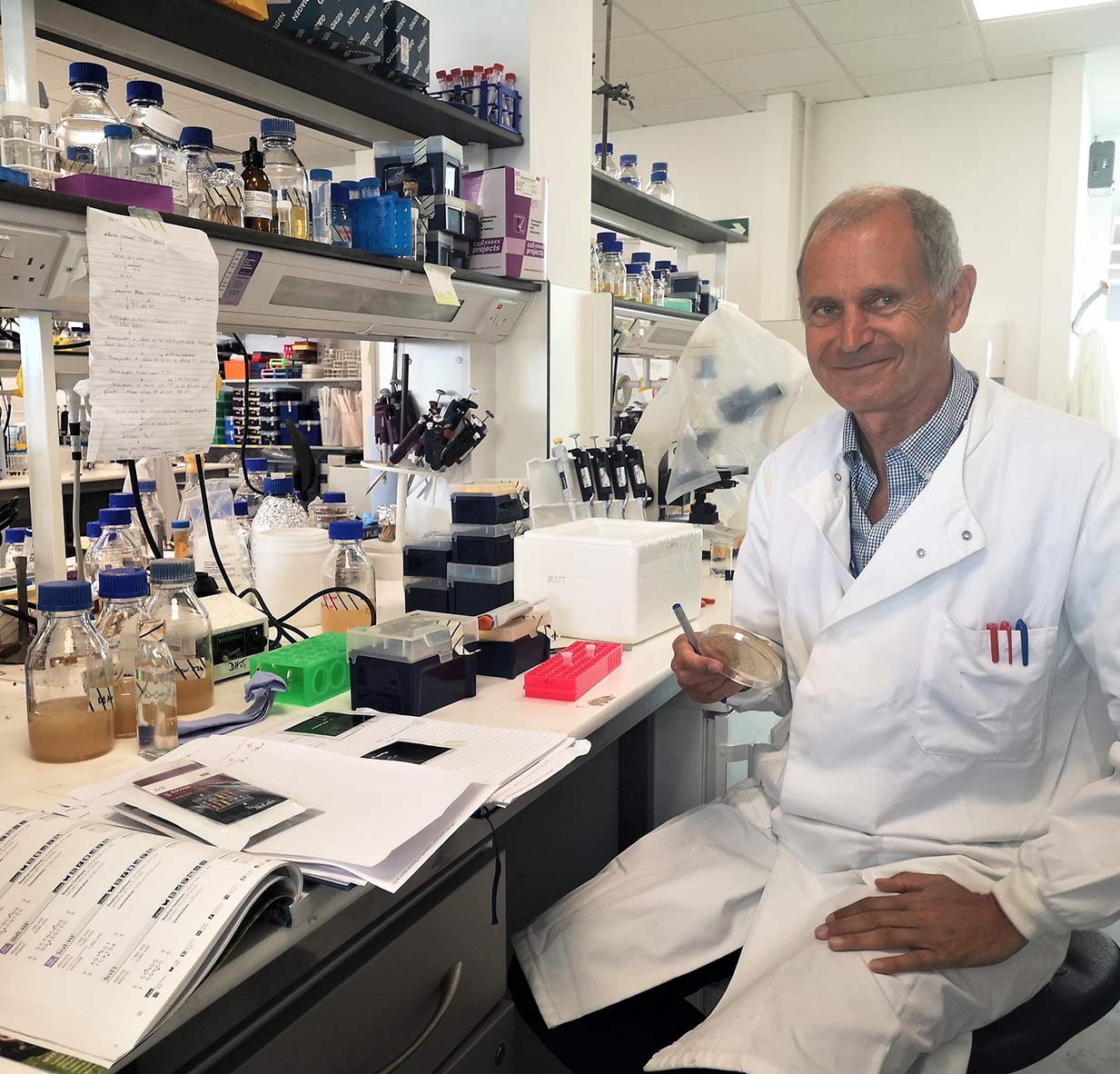

Professor Dyson has developed a technology whereby these symbiotic bacteria deliver information to silence target genes in their insect host.

For example, the technology has been applied as a type of birth control in a blood-feeding insect, the ‘kissing bug’ that transmits deadly Chagas’ disease to human populations in South and Central America. This way the female insects no longer produce viable eggs and the bacteria are spread through the insect colony, but only the target species is affected.

The technology offers two-tier specificity due to the nature of the information produced by the bacteria and the ability of the bacteria to only colonise the host species.

The technology can also be put to use to protect beneficial insects. Scientists in the USA have recently applied it to protect honey bees from the mites that invade their hives and spread a bee virus.