By Alice Peters

I am currently studying for a PGCE in English at Swansea University and have almost finished my first teaching placement.

I’ve quickly realised that Sherrington’s and Oli Cav’s Learning Walk Thrus are central in many schools in Wales, and rightfully so. They are derived from influences such as Rosenshine’s Principles of Effective Instruction (2012) and bestow the importance of key strategies like questioning and active participation. However, there is one questioning technique that has had all of us English PGCE students talking recently: ‘Think, Pair, Share’.

What is ‘Think, Pair, Share’?

Originally created by Professor Frank Lyman in 1981, ‘Think, Pair, Share’ is arguably everywhere. Highly praised by educators as a transformative technique for questioning, it is a popular strategy that fosters collaboration between peers to discuss and develop ideas. It is a pretty simple strategy. Presented with a question or idea, students have time to think about it independently, discuss with a partner, and finally, share with the class.

Sounds fantastic, so what is the problem?

I was surprised during university the number of PGCE students that had felt similar feelings to myself whilst on placement one. Some felt that the ‘think’ time is lost, or the ‘pair’ part causes off task behaviour. Some felt that the students were not gaining anything from the ‘share’ part.

So, what did I do?

“Something really obvious but worth spelling out!”

(Sherrington, 2012)

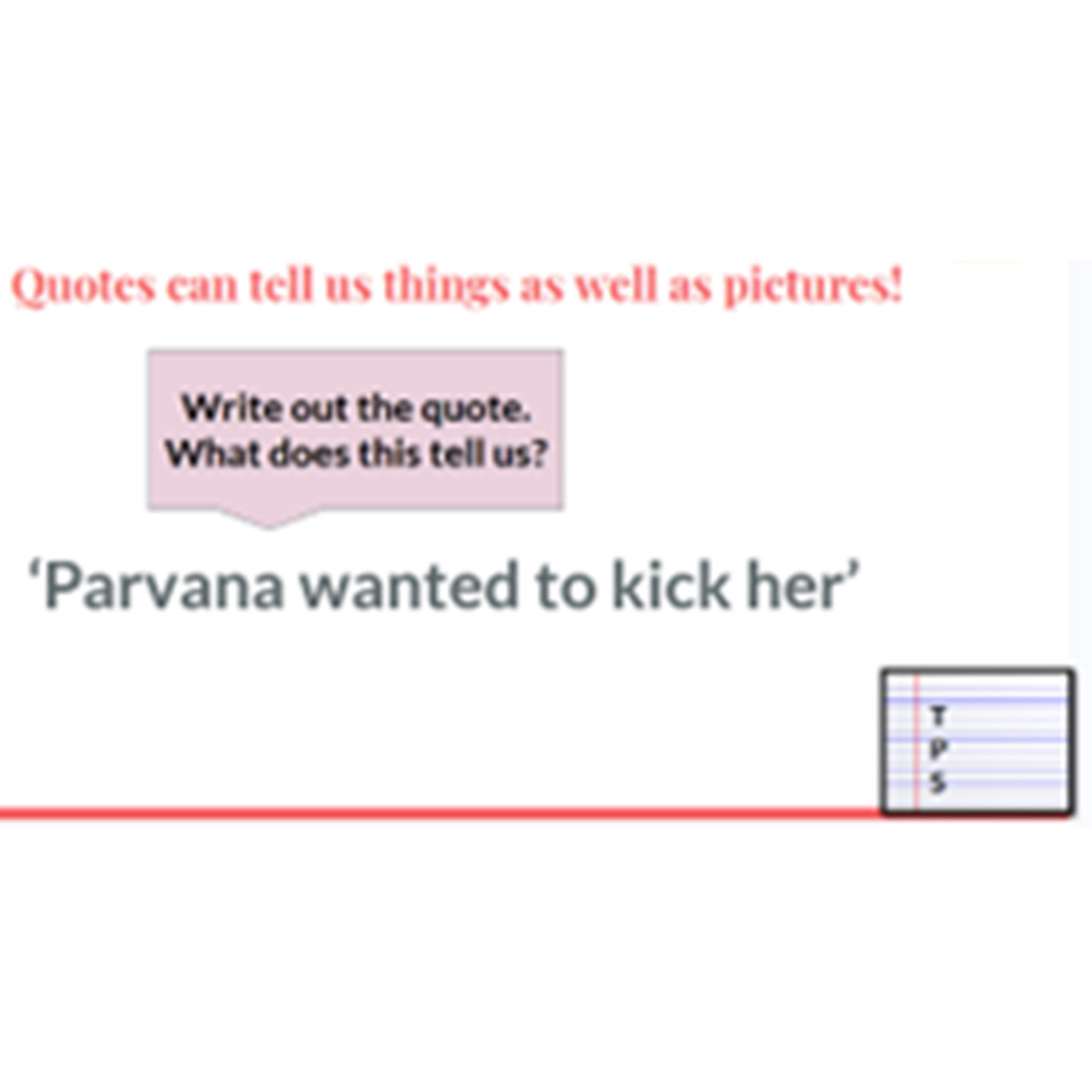

I built in an element of student accountability, in which students are given specific time to organise their thoughts onto paper. Students will activate prior knowledge, not just by thinking but by putting pen to paper. Afterall, when students are writing, they are thinking. I have embedded routines around this approach. As part of the classroom culture, whenever I say ‘Think, Pair, Share’ now, pupils write TPS in their margins and wait for the count down that initiates the ‘Think’ time.

I first trialled this with a busy year seven class and saw its potential instantly.

Circulating allows for you to monitor initial student responses during the thinking time – not just in terms of task compliance but in terms of quality. Having something written down is immensely beneficial, as it gives all students a foundation for discussing with their peers. During ‘Think, Pair, Share’ in my lessons, students are accountable for having something valuable to share. Collaborating with their partners provides a further opportunity for students to consider others’ views before settling on a view themselves. Having a set structure makes it more meaningful and purposeful for all students, and this has had a positive impact on the overall quality of ‘Think, Pair, Share’ outcomes.

Here is a breakdown of how I am currently using this nifty strategy:

THINK

I allow just thirty seconds for students to silently write down their own independent thoughts in the T section. The short timer I use keeps students focused, whilst under a bit of pressure to jot down any ideas they may have. I usually exaggerate that they will be sharing ideas with one other; this seems to help reinforce the importance for students to complete the ‘Think’ part in silence and independently.

PAIR

I count down and we move to ‘Pair’. Students then have a minute precisely to discuss what they have written and share with their partner. I think keeping the time allowed limited here helps to mitigate against off-task chatter and behaviour. A key difference here, perhaps, in my approach is that I expect them to write down their partners’ ideas. Why? It elevates this part of the strategy and makes students accountable for listening to and reflecting upon others’ ideas, too.

SHARE

I personally like using Cold Calling for this section. As Doug Lemov (2010) states in ‘Teach Like a Champion’, it is a positive tool that encourages participation within all lessons if done consistently. It ensures all students have been engaged in the previous parts of the task, with the uncertainty of who will be picked.

This is when a student shouted out, “We steal them!” I just rolled with this, and it stuck.

Once, when in this midst of this set routine, a student shouted out, “We steal them!” I just rolled with this, and it stuck! For my year seven class especially, we now call the task ‘Think, Pair, Steal’.

The addition of ‘Steal’ helps to create a competitive element to the task, and it prompts students to evaluate the quality of pupils’ responses more deeply before they choose who to steal ideas from. From using this adaptation, I think it is a fun way to organise whole class feedback, in which students can further question ideas and push for further reflection.

Student responses have shown definite improvement. By writing initial thoughts onto paper, discussing and sharing ideas, and writing further points down as more knowledge is shared from the class, students are really encouraged to develop their thinking. The best thing is that it has dramatically improved student participation within post ‘Think, Pair, Share’ or ‘Steal’ discussions.

When discussing this strategy with my peers whilst at university, I was struck by the overwhelmingly positive responses. Many PGCE students in my cohort – having also felt the struggle of keeping students engaged and questioning how to improve the effectiveness of this ubiquitous strategy – want to implement this more structured approach within their own teaching.

Leveraging research and strategies is essential for progress. However, it is equally important to adapt and expand upon these approaches as a research-informed, critically reflective practitioner. This mindset does not just enhance the learning experience for students in schools; it also plays a key role in fostering the growth and development of teachers-in-training, like me.