These articles are now archived and will no longer be updated.

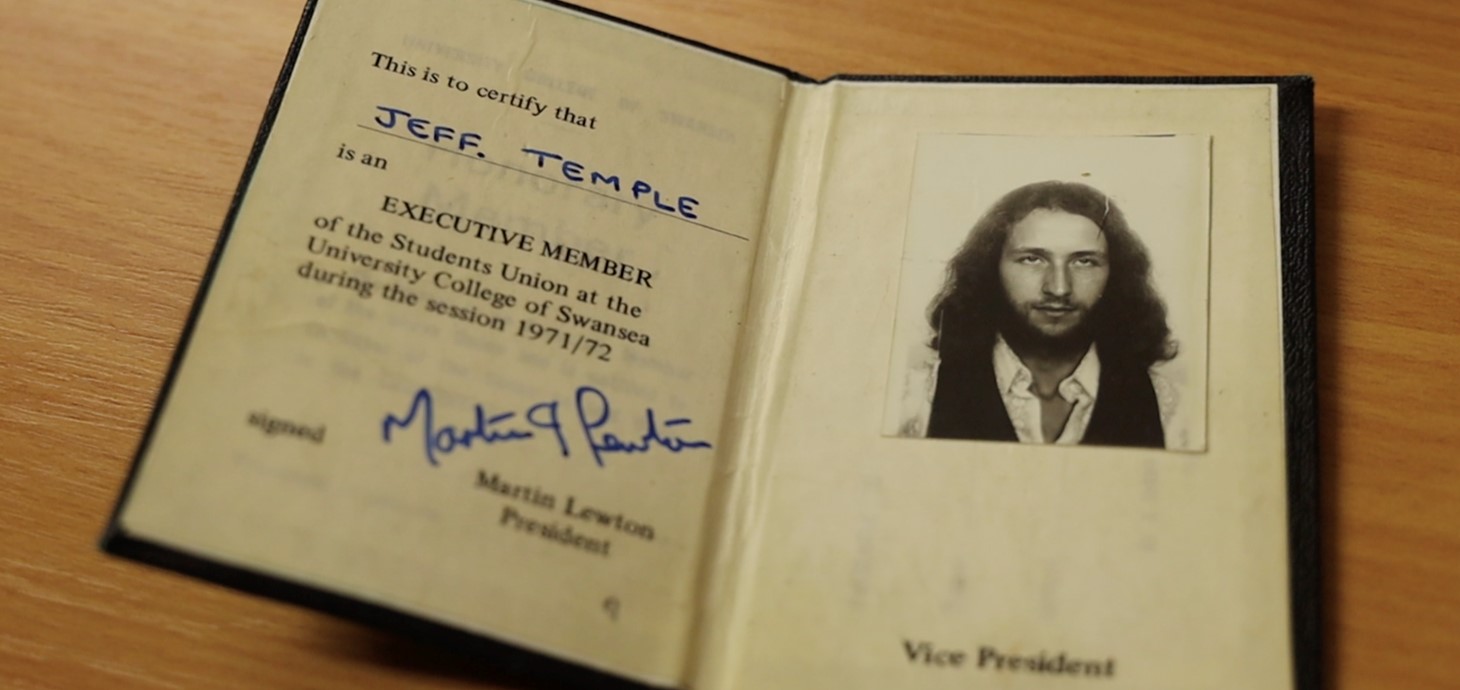

Jeff Temple’s Students' Union membership card from his time as vice-president.

Swansea University has seen thousands of students pass through its doors in the past 100 years, but few can have had a more eventful time than Jeffrey Temple.

From taking on the authorities to being arrested at the infamous Battle of Swansea anti-apartheid protest, activism was central to his time in Swansea. And along the way he even got to lend Paul McCartney his office.

Jeffrey, who came to study chemical engineering in 1969, returned to the University as it marks its centenary to hand over mementoes from his remarkable time as a student

Coincidentally his own stepson has now followed in his academic footsteps and is studying a computer science degree at the University.

Jeffrey’s haul of photographs, rag mags, exam papers, cuttings and Students' Union membership cards provides a glimpse of student life half a century ago.

After presenting his collection to Swansea University archivist Emily Hewitt, Jeffrey and his wife Nadya were given a tour of where his material will be stored.

Jeffrey also returned to the library where he had studied long and hard. After spending his initial years engaged in activism, he joked:

“At the end I fell in with a crowd who were hard working and ruined it all - I ended up getting a 2:1.”

Jeffrey, who graduated in 1973, said his BSc launched a successful international career.

“In 1972 I got a summer job at an oil refinery in Spain. We started at 8am, finished at 2pm and went to the beach. I thought if that is what chemical engineering is like then it’s the job for me and I’ve never regretted it.”

However, things could have been very different if he’d been prosecuted for his involvement in the anti-apartheid protest held when Swansea RFC took on a touring Springboks side in November 1969.

Jeffrey, who was chairman of the University’s Anti-Apartheid Society, explained that Peter Hain – who went on to become MP for Neath and a Government minister, united the movement as more emerged about the injustices of the Apartheid regime.

“I’d say about 90 per cent of the University were in favour of the protests. Swansea was the first tinder box. It was where the irresistible force met the immovable object.”

The so-called Battle of Swansea was one in a series of demonstrations at the tourists’ matches. It saw protesters clash with police, the club’s stewards and rugby fans. Hundreds were hurt and arrested.

Jeffrey said: “I bought a ticket to the match and at the given signal we climbed over the fence and invaded the pitch. I expected to be arrested and I was. I was 18 and foolish because it could have affected the rest of my life if I had ended up with a criminal record.”

He added: “I came off far better than many of my friends who were beaten up, more by the stewards than by the police. I was tripped over by a policeman, kicked by a couple of officers as I lay on the ground and was then dragged off to the cells.

“My friend was thrown over the pointed iron railings and was lucky to come out alive, he had really severe bruising.”

Jeffrey was held in the cells overnight: “In the end I was charged under the Breach of the Peace Act 1361. They said if I had been arrested, I must have done something wrong. Eventually all charges were dropped, and I came out of it scot free.”

But the protesters had made their point. The demonstration was intended as dry run ahead of the controversial South African cricket team’s planned tour to Britain the following summer. Due to the strength of feeling that tour was scrapped.

The end of the 1960s was a time of great change and Jeffrey says events in Swansea were just a snapshot of what was happening at campuses across Europe.

“Back then there was a huge amount of unrest. Students realised they had certain rights, but the older generation was still looking down on them.”

Feelings were running high, particularly at the all-female Beck Hall in Uplands. “The warden ran it with a very tight rein. She had many rules that would have worked in a public school but were not suitable for adults at a university, including a curfew.”

The Representation of the People Act had just been introduced, reducing the age of majority from 21 so 18-year-olds could buy alcohol, vote, get married and have control of their lives.

“The girls were fed up and they wanted a change. They made the perfectly reasonable request that the warden’s role be changed to bursar – from someone in complete charge to someone providing administrative services and support. That request was rejected and some of the girls were suspended. That was the spark that started things.

"The University’s Socialist Society decided on direct action. Around 50 members marched to the hall and assembled in the common room. We felt they were picking on the minority. Shortly after we arrived in came the College’s Principal and Deputy Principal along with the warden and they told us to get out.

“We voted to come back if the girls were not reinstated. The following day was a general meeting of the Students’ Union. There were about 1,000 students there and the President reminded everyone the girls had only asked for what they were due under the law - the University College was in breach, not the girls.

“The next thing that happened was the suspension of the entire Students’ Union executive. Well, if you want to provoke students you go about suspending their leaders.”

The SU membership reacted to the suspension by organising a strike. “We felt right was on our side. We voted pretty well unanimously to strike.”

Newspapers documenting the events are among the items Jeffrey gave to the archives and they detail support received from outside Swansea, including from leading politicians. Among these were Tony Benn, then Minister of Technology, who came down to talk to the students.

They also received backing from civil rights campaigner Bernadette Devlin, at the time the youngest MP and the youngest woman elected to the Commons.

“She was one of us, she looked like us, she was our sort of age and she said ‘I’m with you, lads’. She was the revolutionary firebrand of the day and she came down and supported us.”

The strike lasted 11 days until the University relented, reinstated the students and changed the rules.

Jeffrey’s activism continued during a national student protest when he was among a group of students who occupied the University’s administrative headquarters at Singleton Abbey for a night.

“In my first year I was probably protesting more than I was studying. Looking back my head of department was very tolerant.”

Jeffrey served on the executive committee of Students’ Union from 1971 to 1972, was on the Students' Union Council in 1970 before going on to become vice-president – roles which gave him useful skills.

“To have 1,000 people in front of you and to keep order is quite a challenge but it’s fun. It gave me confidence in public speaking later in my life and taught me many lessons.”

One of those would be how to deal with a megastar musician looking for somewhere to change.

In February 1972 the country was plunged into darkness several times a week as power cuts became a consequence of the Government’s stand-off with the National Union of Mineworkers. At the same time, former Beatle Paul McCartney had just formed his new band Wings and embarked on a brief, low-key tour of UK universities.

Jeffrey, then vice-president, said: “One afternoon – on a day when we did have electricity – we got a call asking if they could come to play at Swansea that night. Just like that!

“Word spread like wildfire - within an hour there was a queue of a thousand people outside the building. We organised everything and then he arrived and came up and changed in my office.

“He said ‘Hi man’ and I said ‘Hi Paul’. It was amazing – one of those things. I was just so privileged to be there at that time. It didn’t cost us anything but there they were, doing their show with us in Swansea, it was absolutely fabulous.”

Jeffrey went on to marry fellow student Gillian Thomas at Swansea’s Guildhall in 1974 and have two children while enjoying a successful career which took him all over the world. But he says his affection for the city endures.

“Leaving Swansea was the biggest wrench of my life. I love the place. Three days before my finals I went walking on Gower and I am sure that helped me get the result I did, because I went into the exam refreshed and relaxed.”

Sadly, his wife died in 2013 but with her family still living in the area Jeffrey has always retained a link to the city.

“My children would come and spend time down here and we have incredibly happy memories.” Jeffrey added: “I have never ever forgotten Swansea and I have used what I learned here throughout my career.”

After his wife’s death Jeffrey became involved in a voluntary work in Kazakhstan where he had worked previously. His role with a charity there led to him meeting his second wife Nadya.

Now living in Tadworth in Surrey, Jeffrey says he did not exert any influence on stepson Dima’s choice of university.

“He was just drawn to Swansea and is really enjoying his course. It is great to be able to come back here and see so many familiar places.

“I really feel my items have gone to such a good home. It feels appropriate they end up here. My degree has been my passport throughout my career, it has taken me round the world, many times. I have so much to feel very grateful to the University for.”